Ottakring and Hernals are situated on the Eastern slopes of the Wienerwald, the outskirts of the Alps. Two important aquifers make their way below these districts towards the center of the city. These aquifers are crucial for the health of the ecosystems in those districts.

We focused our work and research on the Ottakringer Bach, a creek which provides normally 40-60 Liters per second. However this small but temperamental source of water swells up to 200-fold capacity after heavy rainfall, historically this lead to numerous floodings.

This provoked the imperial bureaucracy to put the creek underground into a concrete corset.

Since the 1840's the inhabitants of Ottakring cannot see the rivulet that once provided the area with water.

Since the 1840's the inhabitants of Ottakring cannot see the rivulet that once provided the area with water.

Taking up some concepts of the garden city, from Tel Aviv and Chandigarh, we challenged ourselves to integrate a flowing river which is affected by regular floods into the urban fabric. We wanted to use the natural water source to create a green public passage which runs along the original aquifer crossing the urban infrastructure that was developed above it. However, for us it was not about re-naturalization, but to give precisely defined spaces to local ecosystems for independent development.

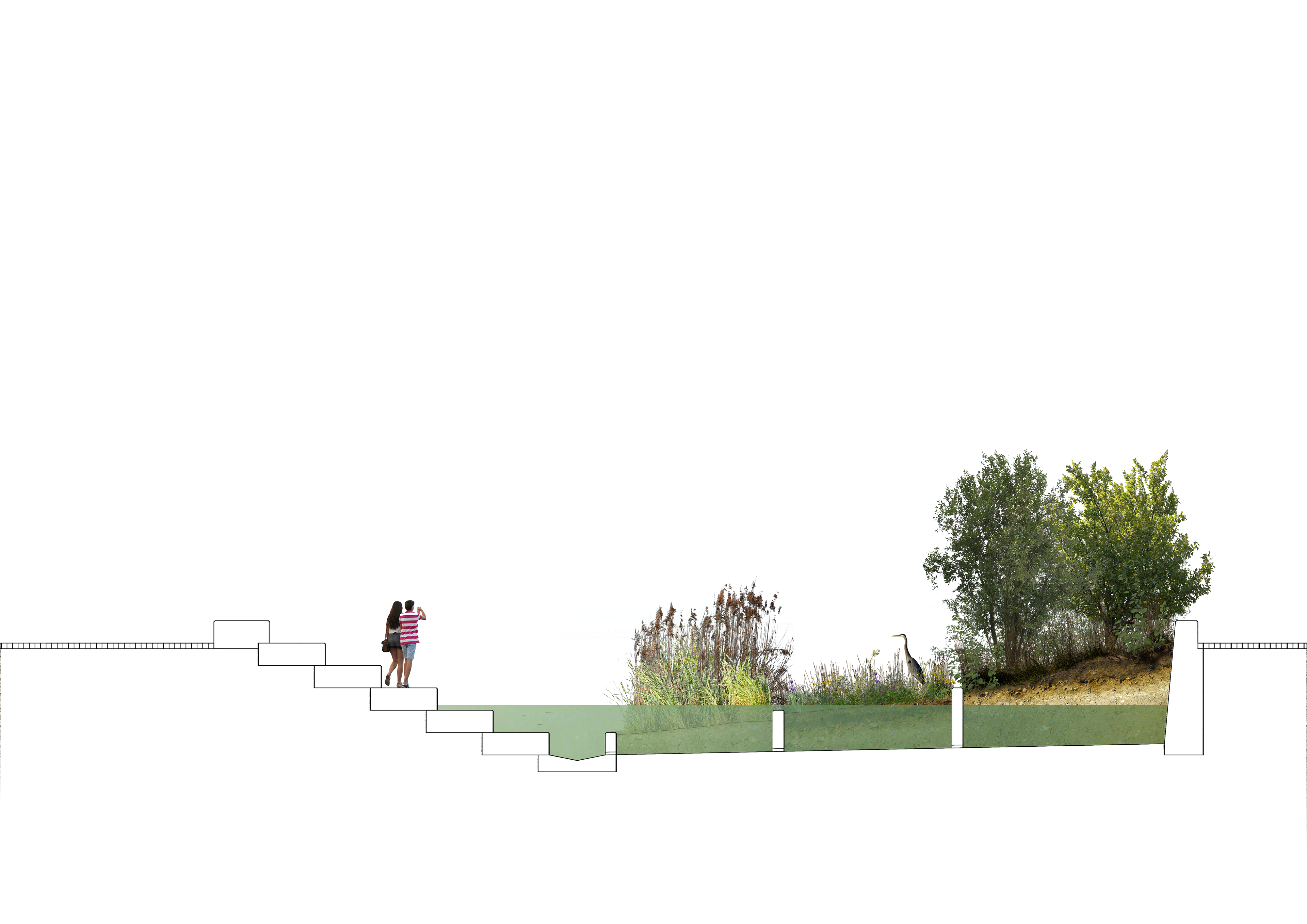

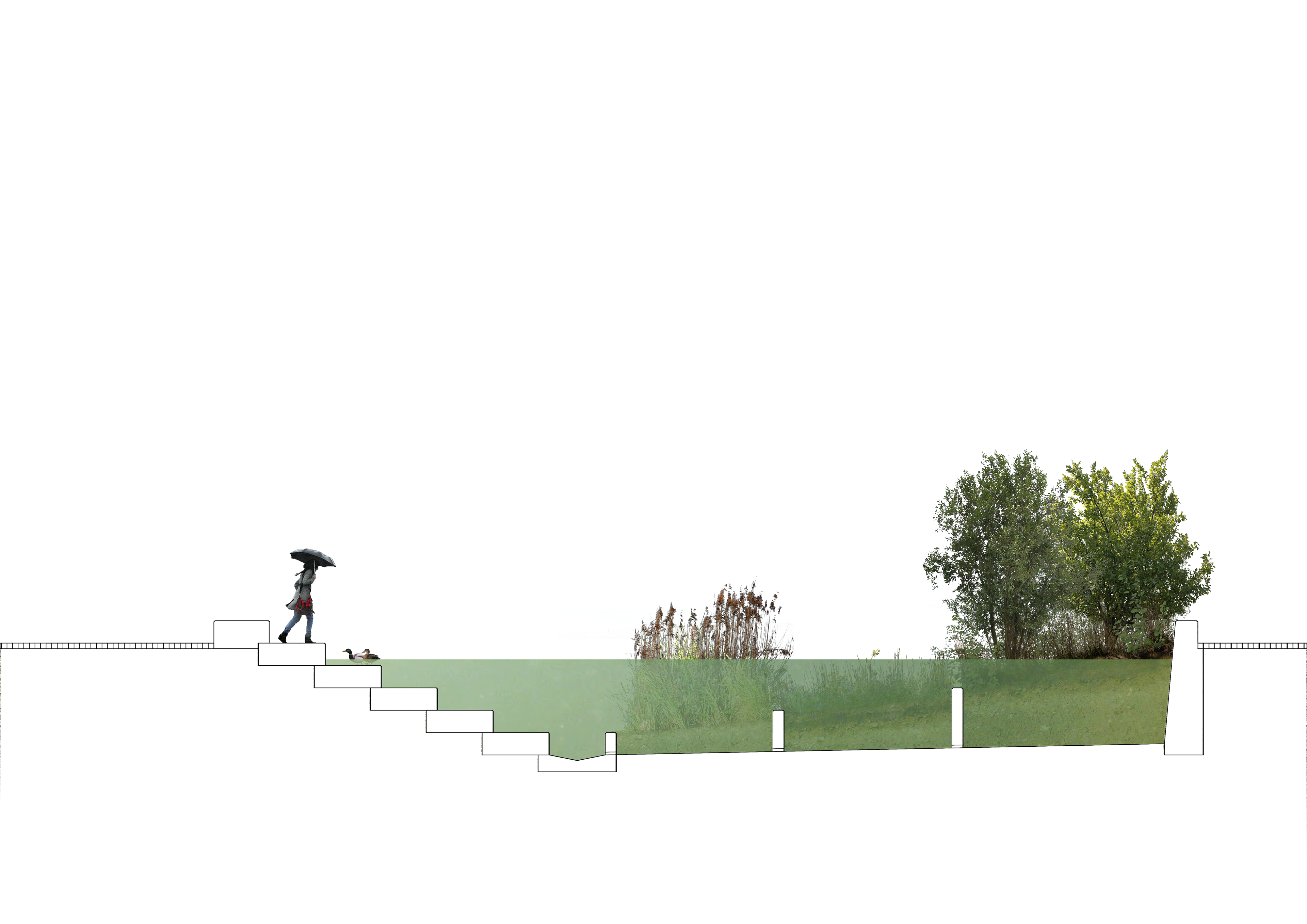

We looked at the natural course of rivers, how the move from the mountains to the plains, passing through different stages and ecologies. It is always important for rivers to have flooding-areas that can absorb excess rainfall.

This inspired us to structure the now revealed canal in three different stages, from a narrow fast running path uphill, to a broader, longer middle area, and a wide passage that ends in a flooded courtyard.

From the very beginning of our exploration we were drawn to the block that surrounds the primary school in Grubergasse. There the river used to run through the interior yard of a farm probably powering a mill.

We decided to focus on this block with its two interior yards, surgically removing the ground floor of three buildings to open the area for the public.

We decided to focus on this block with its two interior yards, surgically removing the ground floor of three buildings to open the area for the public.

It was important that we do not change the nature of Ottakringer Bach, but to integrate its regular floods into the intervention. The public spaces will change their appearance, program and accessibility with the weather and make the changes of the ground water tangible for all to see.

The heavy rainfall will affect the health and composition of the different ecosystems, which depend on rising and falling water.

Similar to the original riparian ecosystems that followed Ottakringer Bach several centuries ago we created spaces for reed-belts, wet meadows and riparian forests, bringing the former inhabitants of Ottakring back and integrating them side by side with its current residents.

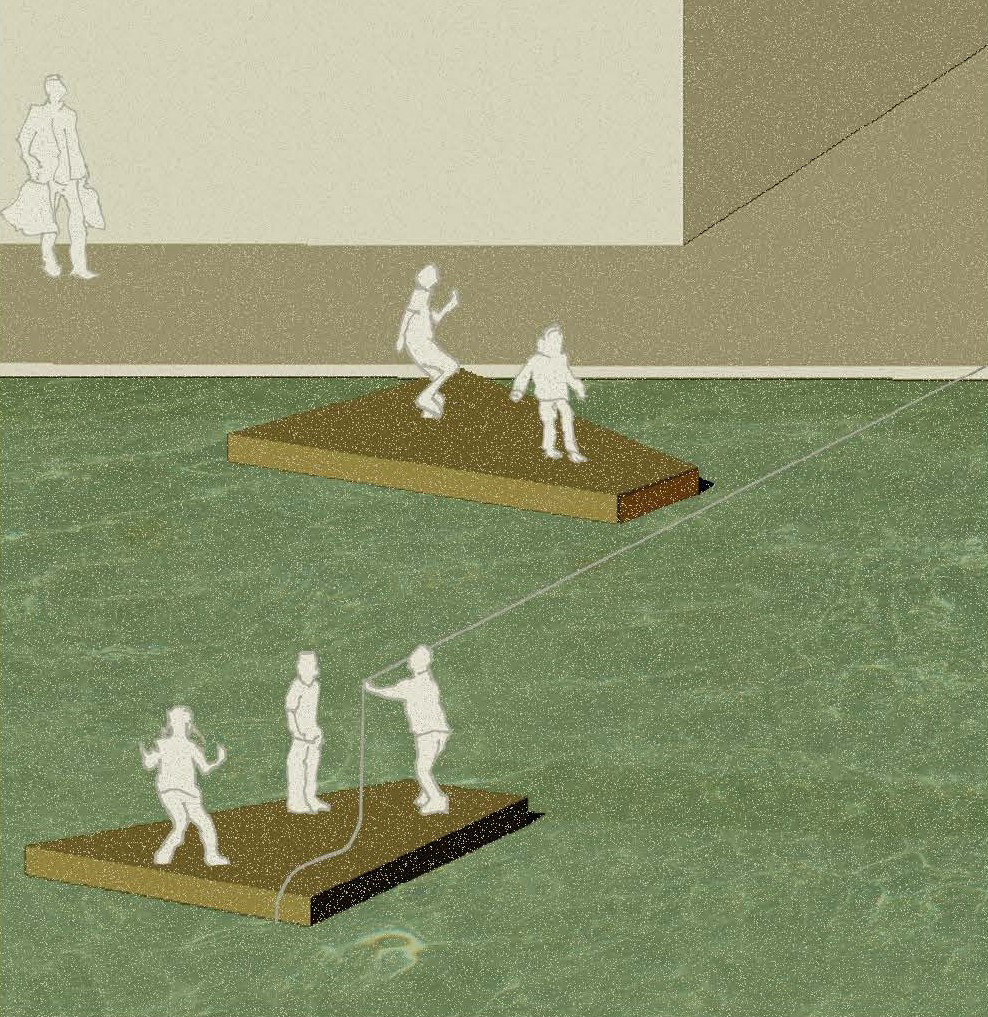

Climate change will lead to the aggregation of rainfall on fewer days but with the same amount of precipitation. This will overwhelm the canalization system. Instead of building new canals, we want to create “supervised” floods that can be experienced by the public and change a natural disaster into fun. In addition, this keeps the rainfall longer in the city and helps to cool down longer heat periods.

It is crucial for children to learn about natural cycles, not just in an abstract, but in a tangible, concrete way, to know with which plants and animals, they co-inhabitate the area. The city with its sealed ground and domination of human-structures makes this quite hard. That’s why we created spaces for them to experience their natural surroundings in an urban way.

We cannot reverse the past, but we need to give space to the non-human actors with whom we share the space.